His first break came in 1972 when he wrote Everybody Rejoice, a song that was included in the Broadway musical, The Wiz. He left school and spent a year at Western Michigan University, where he studied engineering, before he returned to New York City and a career in music. Throughout his teen years Vandross was obsessed with music, particularly Diana Ross and the Supremes, and he spent all his spare time writing and arranging and forming bands among his friends. His father died of diabetes-related problems when Luther was seven, and his mother, who worked as a nurse, raised her two boys and two girls with a stern fist. Luther Vandross was born in New York City in 1951, and grew up in the Lower East Side and then the Bronx. When Vandross appeared on the scene at the start of the 1980s it was immediately apparent that not only did he fit squarely into this tradition of vulnerability, he also possessed both a God-given voice and technical brilliance as a producer/arranger. These men were unafraid to expose their bewilderment and despair, and soulfully lay bare their helplessness in matters of love.

Nat King Cole and Billy Eckstine illuminated the middle years of the 20th century they were succeeded by a posse of mellow-voiced balladeers, including Sam Cooke, Otis Redding, Donny Hathaway, and Al Green. However, it is only relatively recently that African-American men have begun to introduce such painful narratives of loss in love into their own music.

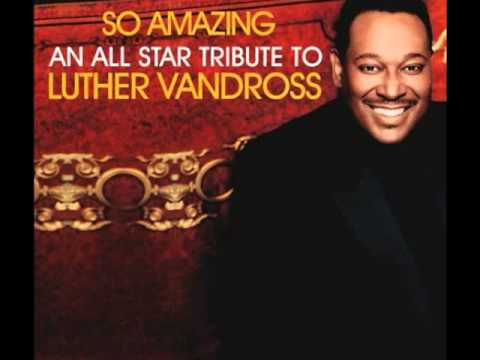

LUTHER VANDROSS LUTHER VANDROSS SONGS HOW TO

In such circumstances, it was difficult for black men or women to know just how to love each other.įemale singers from Bessie Smith to Billie Holiday, and through to Aretha Franklin, have taken up the challenge of singing about difficulties with men who have simply let them down. In this system a man's bond with his wife was always liable to be undermined and broken, because his master could choose to sell the man or woman to different owners in far-flung parts of the country or, even worse, force himself upon the woman. Any possibility of reconstructing a new narrative of loving responsibility was further disrupted by the grim realities of American plantation slavery. After all, the participation of Africans in the American world was preceded by the tearing asunder of lovers and families, first on African soil and then during the middle passage. The theme of thwarted love, familial and romantic, forms a strong line in the African-American narrative tradition. Stevie Wonder paid his own tribute in words and then sang a heart-rending version of the gospel I Won't Complain, while the younger generation was represented by, among others, Usher and Alicia Keys.Įighteen years ago I witnessed a similar demonstration of love and sorrow, some few blocks away at the Cathedral of St John the Divine, when I attended the funeral of the writer, James Baldwin, a man who, like Vandross, was utterly convinced of the refining power of love.

Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton were present, as were the women who had been so significant in Vandross's career: Dionne Warwick read the obituary, while Patti LaBelle, Cissy Houston and Aretha Franklin all took their turns at the microphone and sang. It quickly became clear that this was no ordinary service.

A few weeks ago, I lined up for two hours in the driving rain outside Riverside Church in upper Manhattan in order to pay my respects at Vandross's memorial service.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)